Museums aren’t what they used to be. Once reverential homes for dusty objects in glass cases, they’ve now become places to reconsider dark chapters from the past in a modern light – like at New York’s Tenement Museum and the 9/11 Memorial. The same will soon be true in Ossining, with the arrival of the Sing Sing Prison Museum (SSPM).

The idea for a museum at the maximum security prison was first discussed some thirty years ago, but now it’s a reality, with plans and funds, and an opening date set for 2025, which will be the 200th anniversary of the facility’s existence. ‘The timing is right, with the country addressing criminal justice issues,’ comments Robert Elliott, President of the Sing Sing Museum Board. ‘This will be a story of the past and present through many eyes – a project that brings in the area, the perspective of inmates and their families, the correctional officers, and others too.’

It was in 1825 that the State of New York appropriated $20,100 to purchase a 130-acre site on the Hudson River for what is now the Sing Sing Correctional Facility. It would be the third prison built in New York state, and the original building – the one which will form the core of the museum – was constructed by 100 convicted criminals who dug the stone, known locally as Sing Sing marble, from a quarry that is still within the prison complex.

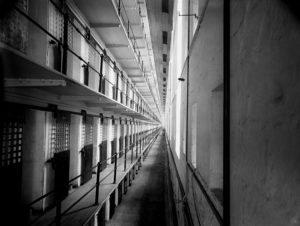

That building, long and narrow, took three years to build. There were four floors and the thick outer walls enclosed the central block of cells, two rows, back to back, each no bigger than seven feet deep, three feet three inches wide and six feet seven inches high. Later another two floors were added, taking the total number of cells to 1200. There was no electricity, no plumbing, no heat, no running water. Health risks for inmates and staff alike were significant.

That building, long and narrow, took three years to build. There were four floors and the thick outer walls enclosed the central block of cells, two rows, back to back, each no bigger than seven feet deep, three feet three inches wide and six feet seven inches high. Later another two floors were added, taking the total number of cells to 1200. There was no electricity, no plumbing, no heat, no running water. Health risks for inmates and staff alike were significant.

Although intended as a model prison, Sing Sing developed a fearsome reputation. In the early years it followed the Auburn System, forcing the prisoners to work in silence, punishing the disobedient with whippings and confinement. At the end of the nineteenth century, the introduction of the electric chair led to the execution there of over 600 people, including Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, convicted of espionage and executed in 1953.

Although the prison had expanded enormously, the original block had fallen out of use, its ironwork stripped out for military needs during World War II and later its roof destroyed in a fire. It is this monument to old, outdated ideas of incarceration, as well as to the extraordinary craftsmanship of the prisoners who built it, which will be the centerpiece of the museum.

‘We have three objectives,’ said Brent Glass, Senior Adviser to the SSPM and Director Emeritus of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. ‘The first is to tell the story of America’s most famous prison. The second is to inspire visitors to think in new ways about criminal justice and become involved in taking action on current issues. The third is to make a positive economic impact on the community.’

It’s a bold and moving vision, but also one in keeping with the progressive attitude of the facility today, which, under the leadership of supervisor Michael Capra, has an active commitment to education and rehabilitation, leading to low rates of recidivism.

It’s a bold and moving vision, but also one in keeping with the progressive attitude of the facility today, which, under the leadership of supervisor Michael Capra, has an active commitment to education and rehabilitation, leading to low rates of recidivism.

Town Supervisor Dana Levenberg sees huge possibilities in the development: ‘The Museum has the potential to transform our region and become the gateway to tourism in the Hudson Valley. Additionally, the social and criminal justice component of the museum aligns with our values: to find better ways to treat human beings and address crime and punishment in our time.’

The first stage in the museum’s development will be the opening of the Preview Center in a building just outside the prison walls, called The Power House, scheduled for the end of 2020. This will entail the conversion of a derelict 1936 power plant into a multi-purpose site that eventually will offer lecture and exhibition spaces, a theatre and a roof-top terrace looking on to the Hudson – but not the prison. Security and privacy issues have been paramount at every stage of the museum’s plans.

The Power House will also be the entrance to a passageway through the prison wall, leading to a viewing space within the original cell block. It’s planned that the block itself – with some of its original ironwork still in place – will remain as it is today, an echoing shell, desolate yet strangely beautiful, like Mr. Rochester’s home after the fire in Jane Eyre.

The plans for this new venue are intensely respectful of everyone involved, from the facility’s staff to its resident population. They also contrast starkly with the treatment of the prisoners when the original block was built, and that’s a large part of the museum’s message.

When asked about any opposition to the museum, Village Mayor Victoria Gearity commented, ‘Questions I’ve heard usually involve concern that the museum intends to exploit incarcerated people as a tourist attraction, which is not the case. It is critical that we create opportunities to help folks understand that a central mission of the museum is to challenge us to imagine a more equitable criminal justice system, and take action toward a more just society.’

‘The histories of the village and the prison are inextricably linked,’ adds Gearity. ‘The museum elevates this relationship.’ And Ossining, already doing a great job of transforming itself with new developments and restaurants, will take another huge step forward with the opening of the museum, just a few minutes away from the Metro North station and easily accessible by car or ferry. Add it to your already long list of desirable places to visit in the Hudson Valley.

To learn more about the history of Sing Sing Prison, visit the exhibition at the Joseph G. Caputo Community Center in Ossining, or the museum’s website singsingprisonmuseum.org.

To read an inside account of life in Sing Sing, see our story on former Sing Sing Chaplain Ronald Lemmert’s book Refuge in Hell: Finding God in Sing Sing HERE.

Closing Sing Sing is not part of the Museum plan. As your article correctly stated, the Museum will be built in the vacant 1936 Powerhouse outside the prison wall, with a connection by a secure corridor into the north end of the 1825 Cellblock. Sing Sing Correctional Facility will continue to function as a maximum security prison, unless NYS Department of Corrections and Community Supervision should at some future time decide otherwise.

The prison museum is a terrible idea. Although real estate people and developers – along with the local politicians would expect to get their cut – have been trying for years to shut down Sing Sing and turn the site into luxury condos, they’ve spun it that this is somehow a progressive move that has the interests of inmates in mind. In fact, all it means is the families of inmates – the vast majority of whom live in NYC and do not drive – would have to travel to Dutchess County or as far away as the Canadian border to visit. Meanwhile, expect that the disposition of the site will be as open transparent and fair as the usual processes are here – in other words, crooked as hell, with a solid screwing for taxpayers at the end of the day.

I’m all for closing prisons. But if NYS wants to start doing that, start with Attica and some of the other gulags in the northern NY tundra. Close Sing Sing LAST, not first.