If you want to delve further into the history of the Old Croton Aqueduct, which lies just below the trail that winds through these river towns, head to a new exhibit that opened recently at the Keeper’s House Visitor Center on the trail in Dobbs Ferry.

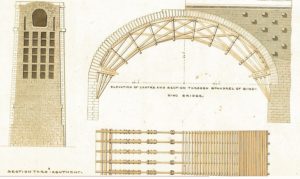

The show features a trove of reproduced drawings not seen by the public in over 175 years. Focusing on important components of the original Croton system, it expands on a prior exhibit, “The Tunnel: A Passage Through History.” Early architectural drawings and renderings produced by draftsmen in the 1830’s are augmented by maps, illustrations, and current photos. These drawings have only recently been digitized, especially those from the Jervis Public Library in Rome, N.Y. The library houses the personal papers of the Chief Engineer, John B. Jervis, the man most responsible for making the Aqueduct a reality.

The displays, mounted on large Plexiglas panels in one room, divide the show into six parts: the original Croton Dam (now submerged), the Ossining Arched Bridge, the High Bridge, the Receiving Reservoir (beneath the site of Central Park’s Great Lawn), the Distributing Reservoir (replaced in the early 1900’s by the 42nd Street library), and a double panel featuring a miscellany of important construction elements. Three prominent items are a large reproduction of an 1851 map of Manhattan and two mid-19th-century bird’s-eye-view illustrations. A small digital frame on one table runs a series of mostly text blocks taken from contemporaneous reports, letters, and an 1855 diary of a nine-year-old girl named Catherine Elizabeth Havens. The diary describes her impressions of the Aqueduct at the High Bridge as well as stories from her family of the bygone days when Aaron Burr’s Manhattan Water Company provided the city with brackish water.

A letter from a Croton engineer, Fayette Bartholomew Tower (acquired courtesy of the Manuscripts and Archives Collection of the New York Public Library), describes, in gushing terms, watching water gush into the Receiving Reservoir for the first time on July 4, 1842:

“At an hour when the morning guns had aroused but few from their dreamy slumbers, and ere yet the rays of the sun had gilded the city domes, I stood upon the topmost wall of this reservoir and saw the first gush of the waters as they entered the bottom and wandered about as if each particle had consciousness and would choose for itself a resting place in this palace towards which it had made a pilgrimage.”

One purpose of the show is to demonstrate just how vital the Aqueduct, by providing desperately needed water, was in enabling New York City to grow so rapidly. In a mere 30 years after the water started flowing in 1842, the city surged northward, past the original reservoir on 42nd Street, up to the 90’s and beyond. And the population soared from 300,000 to one million, in part because of the availability of “pure and wholesome” water.

The result of this explosive growth was that within three decades that first Aqueduct simply couldn’t keep up. By 1890 a new aqueduct was built, capable of delivering three times the water. The Empire City soon outgrew the New Croton Aqueduct (which is still in service), with two more conduits built in the 20th century to bring water from west of the Hudson. But that is for another show.

You can see the show on weekends from 1 to 4 p.m. through the spring. And for maps, tours, walks, and more, go to aqueduct.org.