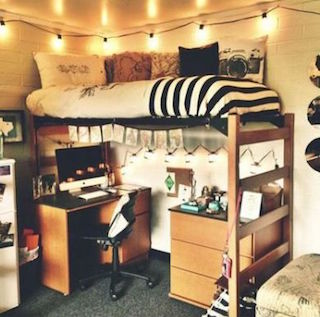

This is the time of year when so many 18 year-olds set off to launch their new lives in college dorms. Every year at this time, I see a few of my young patients go off to school. I know most will be fine, but they aren’t usually as sure of this. I know that even those who won’t fare well immediately will still be fine in the long run, even if the process includes academic probation, dropping classes, or even taking a semester off to regroup. Most of us grow up eventually and find our places in the world, and while some do it more easily than others, the vast majority of us get there sooner than later. I already had a short phone call with one of my young charges, who, barely a few days in her new environs was feeling anxious and conflicted and wanted to check in. Thankfully, nothing she was going through was that significant—making a choice about joining an activity that might be too much of a time commitment for her first semester at school, enjoying her classes so far, but wondering if she chose the right major, and so on. Sadly for her, there were no Dr. K. words of wisdom this time, except for basically giving her the message, “that’s life.”

This is the time of year when so many 18 year-olds set off to launch their new lives in college dorms. Every year at this time, I see a few of my young patients go off to school. I know most will be fine, but they aren’t usually as sure of this. I know that even those who won’t fare well immediately will still be fine in the long run, even if the process includes academic probation, dropping classes, or even taking a semester off to regroup. Most of us grow up eventually and find our places in the world, and while some do it more easily than others, the vast majority of us get there sooner than later. I already had a short phone call with one of my young charges, who, barely a few days in her new environs was feeling anxious and conflicted and wanted to check in. Thankfully, nothing she was going through was that significant—making a choice about joining an activity that might be too much of a time commitment for her first semester at school, enjoying her classes so far, but wondering if she chose the right major, and so on. Sadly for her, there were no Dr. K. words of wisdom this time, except for basically giving her the message, “that’s life.”

In this conversation, this lovely young adult who wants to do well, who loves her friends and her home and gets along well with her parents and therefore might feel a little homesick, I was struck by something that I think has been brewing in this generation for awhile. There was a sense that this angst, this conflict, this worry about making one choice over another, was something about which to be worried. As if she should NOT feel this way, hardly a week after leaving home for her new adventure. As if she should have moved into her dorm room, attended her first couple of days of classes, and everything should have fallen into place with a certain clarity about the rest of her life from this moment on.

When did we start to send the message to young people that “negative” emotions have to be dealt with immediately? When did we start to send the message that anxiety could be eliminated or avoided? Why would a young adult think that her feelings were so out of the ordinary that she needed to talk to her therapist? Or maybe she wanted her therapist to say, “This is totally normal, don’t sweat it,” which is fine, but why couldn’t she do that for herself?

Working with young people of high school and college age, these are themes that keep coming up. Paralyzing fear stops some kids from looking into colleges, to the dismay of their parents who anticipate a 30-year-old living on their couch, aimless and uneducated.

When I ask kids why they are so hesitant to take this leap and look up some schools, talk to their parents about where they want to visit, they often say it just seems so daunting “to decide what I want to do with the rest of my life.” I try to put things in perspective for them—they are not making decisions today about where they will be at 70, they are merely doing some research as to what majors sound interesting and what seem like reasonable options for a future. Every kid I have ever worked with must know that I changed my major and transferred colleges before completing my education, since I have felt compelled to share this with just about every adolescent sitting on my couch, to demonstrate that indecision at 17 or 18 is not the end of the world, nor is it even unusual. It is NORMAL.

Perhaps we have not asked kids to make choices often enough as we lead them into adulthood. Otherwise, they might be more comfortable with the process. If you join that club or sport and it takes up too much time you may have to quit or better balance your time. If you don’t join you might regret it later when you see how much fun it might have been. Neither outcome is the end of the world. Quitting an activity to focus on school, taking time from something else to better manage your responsibilities, or joining that sports team next year when the opportunity knocks again (we used to be told it would always knock twice, right?), are not devastating outcomes. I often tell kids there are very few decisions you can’t adjust or change later, except, I tell them, giving birth to a baby—they can’t be put back in once they’re out. The ridiculousness of that image often helps them to see that most decisions we make can be win/win, or at least neutral/neutral, and that if we are not happy with the decision, we will often have an opportunity to make changes later.

Earlier today I was chatting with a college friend from my stint in engineering school. He is turning 50 in a few months and two of his three children are away at college, the other to follow soon. We talked about his plans for how he would like his life to be in 15 or so years when he is able to retire, and how he has moved around in his career, only to end up doing much the same thing now, from a different perspective, as he did when he graduated nearly 30 years ago and got a job at IBM. Still the quintessential frat boy, outgoing, good looking, boisterous, and smart, he has spent most of his career in the sales end of the profession, using his engineering background to help various corporations, government entities, and other clients set up tech systems, computer networks, and the like. He works up and down the East Coast, makes excellent money, and often moves from startup to startup, the risk and adventure feeding into his need to avoid complacency. We talked about some of our friends who have been at the same companies or even the same types of jobs for 25 or 30 years, one who has been at IBM since graduation, those who stayed in the design end of engineering all these years, because they liked that stability. We have one friend who got an MBA and is a Vice President at an airline now. 30 years ago we did not know where we were going. I became a psychologist. One guy became an attorney. One is a chef. One works for a bank. One of the other few girls in our group (I believe my school was 90% male) moved to Texas to go to A&M and settled there, working in the STEM fields until she had children, whom she ended up home-schooling through middle school.

My friend and I talked about how you have to adapt to not end up jobless, under-employed, bored, or frantically trying to eke out a living. I have to deal with health insurance and healthcare policy uncertainty. I have to get further training from time to time to keep on top of new theories, research, laws and guidelines. He, of course, has to keep up with new technology. Did our 17 year-old selves back in Downtown Brooklyn realize that our lives would take so many twists and turns? That one could go from engineering school to, at 50, being a corporate chef? That the 38 I got on my first calculus test was not the end of the world, but merely the first sign that perhaps this major was not for me? Maybe, maybe not. But I don’t recall there being so much angst about having angst. My dad wanted me to be an engineer, and I had angst about telling him I had changed my mind, but I don’t recall feeling that this angst was unusual, or that my angst about choosing a new major (Journalism? Photography? Literature? Psychology!) was something to be worried about. Of course I was feeling out of sorts as I figured out my next step, and I talked to my friends about it, and didn’t feel that it was abnormal. After all, when you get to a specialty STEM school as a freshman, they basically tell you that most of you will leave anyway, so maybe we were primed for it when so many of us left for other pursuits.

I love working with young adults launching their lives, and I’m honored to be part of the process. However, I’m not sure we do enough to teach the next generation that angst is normal at this time; it’s OK, and it is to be lived with and experienced, not pushed away like some enemy. Nor can we always have our cake and eat it too. As I said to a youngster the other day, I’d love to have five simultaneous careers, there’s a lot that interests me, but I’m only one person, so I chose one career, and do some other things I like on the side as hobbies, or, like writing this article, or teaching a class, I can do them as a small part of my professional life. Life is about choices. Not all will be easy, but most are not worth losing sleep over. Let’s make sure our young neighbors and friends know that. In that way, they can distinguish an issue that is, indeed, serious and requiring intervention, and what is simply, “just life,” with the choices we make and the speedbumps we hit along the way.

Barbara Kapetanakes, Psy.D. practices psychotherapy in Sleepy Hollow.