Times have changed

Times have changed

And we’ve often rewound the clock

Since the Puritans got a shock

When they landed on Plymouth Rock.

If today

Any shock they should try to stem

‘Stead of landing on Plymouth Rock,

Plymouth Rock would land on them.

So wrote Cole Porter in the American songbook staple “Anything Goes,” the title song of his signature Broadway musical.

I don’t know what shock ol’ king Cole was thinking of, but around the same time he wrote that song, a history buff happened upon the discovery that the pilgrims who landed on Plymouth Rock in Massachusetts 400 years ago on Nov. 11 were not the first to give thanks in a ceremonial way that has resonated to this day.

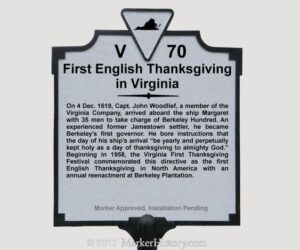

That distinction belongs to a place about 600 miles south of Plymouth, namely Berkeley Plantation, Virginia. The historical “whistleblower” was Lyon Tyler, one-time president of the College of William and Mary, and the son of the 10th President of the United States, John Tyler.

IT’S OFFICIAL

What Lyon Tyler discovered through copious research is depicted in a fascinating 30-minute TV program from the Commonwealth of Virginia Film Office, titled “The First Official Thanksgiving.”

As the story goes, King James I granted to four Englishmen in London 8,000 acres of land along three miles of the James River, on Chesapeake Bay in Virginia.

The plan was to put down roots there to create a settlement — which came to be known as Berkeley Plantation — that would reap cash crops, with the profits sent back to the monarchy.

In the 17th Century, we learn, the word “plantation” (or plantacon) meant transporting yourself to a new life in a new place — in effect, transplanting your life.

To that purpose, an expedition was assembled under the aegis of an English captain, John Woodlief. He recruited 35 able-bodied men to navigate a 36-foot schooner for the arduous voyage, crossing the Atlantic to the New World. They set sail Sept. 16, 1619.

NEW ARRIVALS

On Dec 4, 1619, the good ship Margaret made landfall at the designated settlement-to-be, and the men came ashore on the banks of the James River.

Then, on explicit instructions from England, the settlers dropped to their knees, and gave thanks for safe passage.

With the men gathered around him, in solemn repose, Woodlief recited what was given to him as part of his expedition charter …

“We do ordain that this day of our ship’s arrival at the place assigned for plantacon in the land of Virginia shall be yearly and perpetually kept holy as a day of thanks giving to almighty God. Amen.”

It would be another full year before the fabled pilgrims — who apparently had better PR — landed at Plymouth Rock, and another two years before they held their first Thanksgiving.

FRIENDLY RIVALRY

Over the years, the revisionist revelation unearthed by Lyon Tyler has precipitated some light-hearted moments of friendly rivalry between the original colonies of Virginia and Massachusetts.

When the United States administration of John F. Kennedy in 1962 issued the traditional Thanksgiving proclamation, crediting the President’s home state of Massachusetts with the original Thanksgiving, Virginia state Sen. John Wicker sent off a note of correction.

In response, Kennedy aide Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. wrote back, “You are quite right; and I can only plead an inconquerable New England bias on the part of the White House staff.”

The upshot, to the delight of Wicker and Virginia, is that the 1963 proclamation issued in the President’s name indeed listed first Virginia and then Massachusetts as the twin birthplaces of the holiday that we all love, except for the turkeys among us.

TO THE GOOD LIFE

“What is a celebration of Thanksgiving,” ponders one Virginian in the program. “Is it all turkey and dressing, or is it saying thank you to someone, or to a higher power for a good life or being an American, or whatever.”

Another offers what, at this extremely fraught moment in our country’s evolution, is a timely reminder to take to heart: “We can be most thankful that, in spite of occasional differences of opinion, we are a United States, dedicated to freedom of thought, freedom of expression, freedom of worship.”

“It’s a big day that transcends all the hoopla — the big meals and all that,” says Chief Stephen Adkins of Virginia’s Chickahominy Tribe. “It’s a time to reflect and really take stock of what’s important in life. But don’t get me wrong. I don’t want to stop that food. Bring it on!”