When Gerhard Schmitt took over at the Kolping Society’s 50-acre religious retreat in Montrose, he heard that the property’s previous inhabitant, Louis Perlman, exerted enough power and influence to turn the train tracks away from the river and bypass his waterfront estate.

That cannot be true. Perlman bought the lot in 1915, long after the iron horse steamed up the Hudson to Albany in 1851, spewing coal dust and cutting through onetime lots of private property seized by eminent domain.

It is indisputable, however, that the only place along the river from New York City to Albany where the tracks turn away from the river begins at the border between Oscawana and the Town of Cortlandt hamlet of Crugers. Verplanck is the only riverfront municipality that the train never traverses. Five miles upriver, it hugs the Hudson again after meeting up in Peekskill.

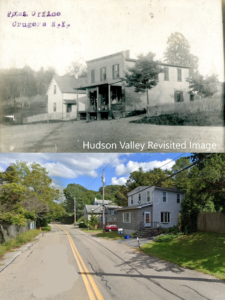

The area around Oscawana Island once included brickyards, light industry, a train station and a post office. Now, it’s a town park. The Crugers name endures: Crugers Avenue, Crugers Station Road and the post office. Montrose had a station, too, until Metro-North consolidated it into the generic Cortlandt stop in 1996.

Determining the real reasons why the tracks veered from the shoreline would be a formidable research project. Perhaps the engineers sought to avoid a sharp turn at Verplanck Point, though they navigated a similar situation at Anthony’s Nose by tunneling under the rock. Local residents hand-blasted the big holes through Oscawanna Island and Route 9A.

Maybe the influential Cruger family (originally spelled Cruger’s and allegedly named for their Crusader ancestors) exerted enough pull to redirect the route and spare their main estates, Belmont and Boscobel, from the intrusion of dirty, noisy steam engines.

Though likely Danish, John Cruger moved to New York City from England in the 1690s and served as mayor. His son, John Cruger II, occupied the same position from 1756 to 1765. One of his brothers, Henry Cruger, became the first American elected to the English Parliament in 1774, just as the Revolutionary War began boiling.

Great grandson John Peach Cruger married well and owned Boscobel when the railroad arrived. Though the home “served as a social center for the region,” according to one local history, things went downhill for the family and the Crugers dispersed after World War I.

In the late 1800s, steamboats began ferrying day-trippers to a hotel and dancing pavilion in Oscawana. Another hotel and restaurant nearby also attracted tourists, but locals gathered at Eddie Rogan’s Bar, located on a houseboat.

By 1884, maybe 20 estates occupied the area, including Long View, McAndrews and Elphinestone. The current owners of Belmont, also known as Laurel Hill House, hang a sign identifying the place. Another large historic home on the hill is invisible from the road during the leafy months.

Built in 1808, the renowned Boscobel mansion, which straddled Crugers and Montrose, fell into disrepair by the 1850s. Local and county entities considered turning the land into Crugers Park, but it’s now the federal Veterans Administration complex.

In 1955, when a wrecker who bought the elaborate home for $35 showed up with bulldozers, preservationists from the Westchester County Historical Society jumped into action, prompting a response from the state police.

Reader’s Digest heiress Lila Acheson Wallace provided a $500,000 grant that kickstarted a campaign to save the house, now located in Putnam County.

One historian reported that in Crugers’ heyday, a “paint factory, a telegraph office, a post office, a hotel, and stores” were clustered near Crugers station, where a rusting steel bridge-to-nowhere still spans the tracks. Through World War II, a dozen estates and another thirty or so more modest homes dotted the landscape.

Over time, Crugers suburbanized as developers subdivided the great estates. Angelo Milano left his mark on Laurel Hill, naming the streets after family members and creating Milano Court.

Another speculator turned the Beinecke-Ogilvie property into Springvale, which opened in 1960 as one of the country’s first privately financed senior living facilities.

The singular stretch where the railroad pulls away from the river between Crugers and Peekskill created the hamlet’s most lasting legacy as trains roared through the countryside and snaked around the large estates.

According to one account, the path sliced through Benjamin Dykstra’s farm “right past the front porch of . . . the family home.” His daughter Jane Dykstra inherited the place, which predated the Revolutionary War.

“Her vigorous attempts to stay the laying of the railroad tracks alongside her veranda brought many a wry smile from her neighbors,” according to a book about the family. Despite their lineage to the earliest Dutch settlers, they “had no money or power to fight.”

Marc Ferris is a regular contributor to River Journal.