“We songwriters deal with 90 percent disappointment,” Jimmy Webb told me during a recent interview. “If you haven’t got a high tolerance for disappointment, you’re in the wrong racket.”

Webb’s disappointments seem to be few. He won a Grammy Award at age 21 and penned chart-topping pop and country songs for many recording artists from the 1960s through the 80s.

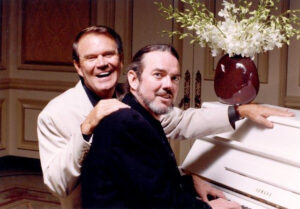

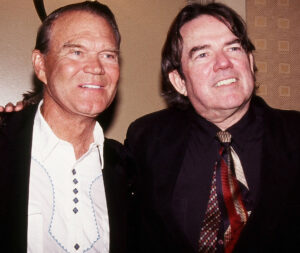

He’s perhaps best known for his association with Glen Campbell. The shaggy-haired young songwriter supplied the clean-cut country singer and guitarist with the Top 10 hits “By the Time I Get to Phoenix”, “Wichita Lineman” and “Galveston”.

The two formed a bond that lasted from the 1960s until Campbell died of Alzheimer’s disease in 2017, and Webb has been honoring his friend with a show coming to the Paramount Hudson Valley Theater in Peekskill on Sept. 22.

“As long as I can play the piano, he’ll never be forgotten,” said Webb, who was inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame in 1986. “That’s why I put this tribute show together.”

The show features Webb performing on solo piano and vocals, sharing anecdotes about his friend and accompanied by a multimedia show that includes a virtual duet, with Campbell playing guitar on MacArthur Park.

Besides the hits, the show includes some lesser-known songs, including “The Moon is a Harsh Mistress” and “Highwayman”.

Webb, who grew up in the Southwest playing organ in his father’s church, lives on Long Island.

Here’s a Q&A with Webb, which has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

River Journal: You’ve been performing these songs for so many years. What keeps it fresh for you?

Jimmy Webb: A song is never finished for me. It’s kind of torture, because years later, I mean 10, 12 years later, I’ll listen to it, and I’ll go ‘Oh man, that line isn’t right, I need another word there.’ That old songwriting machine keeps running all the time, so sometimes I have to suppress that because once something’s out there, it’s out there forever. Sometimes your instincts take over and you do break the rules occasionally, as long as it’s a search for the truth.

I’m constantly writing but I never play anything the same way twice. I’m more of a jazz musician than I am, say, a Billy Joel-type of rock performer, and there’s a lot of improvisation.

RJ: Bob Dylan called Wichita Lineman the greatest song ever written, What’s the backstory?

Webb: In my mind I was back in the panhandle in Texas and Oklahoma where I grew up. It’s this flat, almost featureless landscape except for these telephone wires, they’re a constant companion, they follow you along the road.

When I was a child, we used to stop the car out in the middle of this great silence, in this ocean of nothing, and we’d listen, and you could hear the wires singing. That’s why I wrote, “I hear you singing in the wires,” and so it slowly came together.

One afternoon [Campbell] was in the studio, waiting for me to write a song. Finally, I just worked out a couple of verses. I got kind of tired, I had been on it all day, and I finally took what I had, which was the first two verses, and put them in a manilla envelope with a cassette and put a note in there, “Dear Glen, this song isn’t finished. Let me know if you like it and I’ll flesh it out.” It went off with the messenger.

I walked into the studio about two or three weeks later. I said, “Glen, don’t worry about that Wichita Lineman thing, that was just an idea. I didn’t finish it, but I never heard from you guys.” And he said, “Wichita Lineman? We cut that.” And I said, “Didn’t you see my note, I told you it wasn’t finished,” and he said “Well, it is now.”

The last line, “And I need you more than want you, and I want you for all time,” is a false rhyme. I didn’t realize it until I was writing my book. I can’t go back and change Wichita Lineman, and it’s worked out pretty well.

RJ: You described Campbell in a 1988 interview as being a much better interpreter of your material than you.

Webb: I started as a very shaky singer. I’m proud to say I’ve improved a lot, and I do a lot better job singing my songs now. I’d describe myself as a fair to middling singer. I guess I sing like a songwriter.

[Campbell] was gifted, he had a five-octave range, and it’s pretty awe-inspiring to have that much flexibility.

RJ: You visited Campbell toward the end of his life. What were those visits like?

Webb: It was sad and at the same time it was lovely and wonderful to still have him with us at the end of the ordeal. He was very affable. He could still play the guitar. Every once and while he’d pick up the guitar and play some outrageous lick, that part of him was still very much intact.

RJ: You’re turning 78 this month. How much longer do you plan to keep performing?

Webb: I think I’ll probably do it until I’m 80, and I’ve got at least one more album in me. It’s very difficult to write songs now. I didn’t realize when I was younger how much brain power it takes to write a really good song. But I really have to work at it.

I’ve got 10 Broadway scores in the can that have never grown up. I’ve got a cantata; I’ve got several classical pieces. I never really stopped writing but I’m slowing down, so I get a big kick out of performing, because it energizes me and the audience. I get more out of it than they do.

Jimmy Webb: The Glen Campbell Years

Jimmy Webb: The Glen Campbell Years

7 p.m. Sunday, Sept. 22

Paramount Hudson Valley Theater

1008 Brown St., Peekskill

Free tickets for a song

The Paramount is giving away 10 pairs of tickets to the show, and you can win a pair by sending an email to publisher@rivertownsmedia.com with your favorite Jimmy Webb-Glen Campbell song title in the subject line.